In September 2025, during an episode of the Thoughtworks Technology podcast, Matthew Skelton made an observation that has stuck with me: “Generative AI has the ability to amplify great engineers.” It’s a powerful statement, and one that resonates with many of us who’ve seen skilled developers use AI tools to accelerate their work, automate tedious tasks, and explore solutions more rapidly than ever before.

But as I listened to Skelton’s words, a different thought emerged: if AI can amplify great engineers, what does it do to engineers who aren’t yet great? What happens when we amplify those who lack the experience, understanding, or foundational skills to recognise when the AI has led them astray?

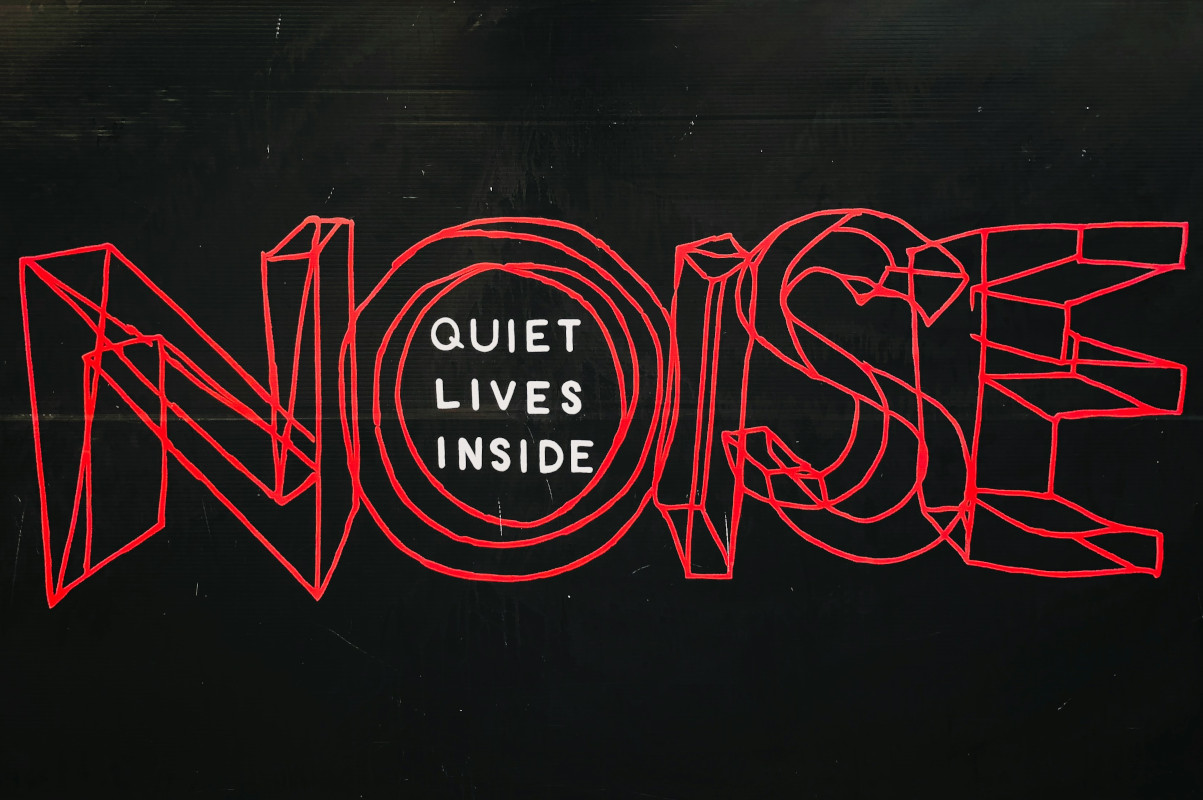

The answer, I’m afraid, is something the internet has started calling “AI slop.”

What Is AI Slop?

AI slop refers to low-quality, AI-generated content that shows a lack of effort, understanding, or deeper meaning. Whilst the term originated in discussions about AI-generated images and social media content, it has found an uncomfortable home in software development. We’re now seeing AI slop manifest as:

- Pull requests containing thousands of lines of code that the submitter cannot explain

- Bug reports generated by LLMs that waste maintainers’ time on non-existent issues

- Security vulnerability submissions that are hallucinated rather than verified

- Codebases bloated with unnecessary files and patterns that no human would reasonably create

The problem isn’t the use of AI tools; the problem is the gap between what AI can generate and what the human wielding it can understand and verify.

A Case Study: 13,000 Lines Without Understanding

In November 2025, a pull request was submitted to the OCaml compiler project that perfectly illustrates this amplification paradox. The PR added DWARF debugging support to OCaml, a genuinely useful feature that the community had wanted for years. The implementation was over 13,000 lines of code spread across multiple files, included comprehensive tests, and appeared to work.

The author was transparent about their process: Claude Sonnet 4.5 and ChatGPT had written essentially all of the code over several days, with the human “directing, shaping, cajoling and reviewing” but not writing “a single line of code.”

On the surface, this sounds like a success story; AI enabling someone to contribute a complex feature they couldn’t have built themselves. But as the discussion unfolded, several concerning patterns emerged:

Attribution issues: Files credited another developer (Mark Shinwell) as the author, raising questions about whether code had been copied from existing work. The submitter acknowledged they’d asked the AI to look at existing implementations but couldn’t clarify what had been used.

Maintenance concerns: When asked about ongoing maintenance, the submitter admitted they lacked funding to maintain the code without continued AI assistance. This raises a critical question: if you cannot maintain code without AI, do you truly understand it well enough to be accountable for it?

Process mismatch: The development approach was fundamentally incompatible with the project’s collaborative practices. As one maintainer noted, the burden of reviewing 13,000 lines of AI-generated code without the usual incremental discussion and buy-in was simply not sustainable.

To be clear: this is not about singling out an individual contributor. The person who submitted this PR was attempting to solve a real problem and was transparent about their methods. The issue is systemic, not personal. It’s about what happens when our tools enable us to create far beyond our ability to verify, maintain, and be accountable for what we’ve created.

The Broader Pattern: AI Slop Across Open Source

The OCaml case is far from isolated. This pattern is emerging across the open-source ecosystem:

Security Reports That Waste Maintainer Time

Seth Larson, security developer-in-residence at the Python Software Foundation, has documented an uptick in “extremely low-quality, spammy, and LLM-hallucinated security reports to open source projects.” These reports appear legitimate at first glance but require significant time from already-stretched maintainers to refute.

The Curl project has dealt with similar issues. In January 2025, maintainer Daniel Stenberg called out AI-generated security reports, stating:

When [security] reports are made to look better and to appear to have a point, it takes a (sic) longer time for us to research and eventually discard it. Every security report has to have a human spend time to look at it and assess what it means.

The better the crap, the longer time and the more energy we have to spend on the report until we close it. A crap report does not help the project at all. It instead takes away developer time and energy from something productive. Partly because security work is consider(ed) one of the most important areas so it tends to trump almost everything else.

Cleanup Work for Startups

Freelance developers are reporting a new revenue stream: cleaning up AI-generated codebases. One European freelancer noted a “large increase in projects where startups paid a ton of money for an AI software and it does not work well at all. Tons of errors, unreasonably slow, inefficient and taking up a lot of resources, and large security flaws.”

In one case shared online, a designer with CSS knowledge but limited programming experience used AI to build a full React application. The startup then hired a React developer to “fix it up,” and that developer removed over 90 of the 100 files the AI had generated.

The Quality Problem

The core issue isn’t that AI generates bad code; it’s that AI generates mediocre code at volume, and mediocre code generated without understanding becomes a maintenance nightmare. As one developer put it: “AI is trained on all the publicly available code. So take all of that code and get the average and that’s what AI is using to generate code… most of the code I see is bad to mediocre and less than 10% is good.”

When an experienced developer uses AI to generate boilerplate or explore solutions, they can spot the mediocre patterns and refactor accordingly. When someone lacks that experience, the mediocre code ships unchanged, creating technical debt from day one.

The Self-Review Trap

There’s a tempting solution to the verification problem: why not use AI to review the AI-generated code? After all, if AI can generate code, surely it can review it too?

This approach is fundamentally flawed. It’s the equivalent of asking a student to mark their own homework. The AI that reviews the code suffers from the same limitations as the AI that generated it:

- It cannot verify that the code solves the actual business problem, only that it’s syntactically correct

- It will apply the same “average of all code” approach to its review

- It cannot catch conceptual errors or architectural issues that require domain understanding

- It has no accountability for the long-term consequences of shipping poor code

Moreover, using AI to review AI-generated code creates a dangerous feedback loop. If both the generation and review are automated, and the human in the middle lacks the expertise to challenge either, you’ve essentially removed human judgment from the process entirely. You’re not amplifying human capability; you’re replacing it.

The review process exists precisely because code needs to be understood by humans who will maintain it, debug it, and extend it. When that understanding is absent from both the generation and review phases, you’ve created code that exists in a vacuum, working today but potentially unmaintainable tomorrow.

Trust, But Verify: What Does Verification Mean?

My friend Jim Humelsine, in his excellent blog post “An Introduction to Large Language Models and Generative AI,” reminds us of the Russian proverb: “trust, but verify.” This principle is sound, but it raises an uncomfortable question: how do you verify code you couldn’t write yourself?

Consider the verification challenge at different skill levels:

✅ Expert developers

They can verify AI-generated code because they understand the problem domain, recognise code smells, can spot security issues, and know what good architecture looks like. AI amplifies their capability.

⚠️ Intermediate developers

They can verify some aspects but might miss subtle issues. They can check if the code works but might not spot inefficiencies, security vulnerabilities, or maintainability problems. AI amplifies their output but not necessarily their understanding.

💭 Junior developers or domain novices

They often struggle to verify effectively. If they couldn’t write the code themselves, how can they judge whether the AI’s solution is good, mediocre, or problematic? They can verify that it compiles and passes basic tests, but that’s far from comprehensive verification.

This creates a dangerous illusion: the code works, tests pass, and the feature ships. But understanding, maintainability, and long-term quality may all be absent.

The Maintainability Trap

During the Safia Abdalla interview on The Modern .NET Show, she made a crucial observation about how we should treat LLMs with the same intentionality we’d bring to human collaboration. When we interact with AI, we’re forced to be clear about what we want, to articulate problems precisely, and to think through requirements carefully.

But there’s a critical difference: when a human collaborator helps you build something, you learn from the process. You understand the tradeoffs they made, the patterns they chose, and why certain approaches were selected over others. With AI-generated code, unless you’re actively learning from what it produces, you’re left with a working implementation you don’t truly understand.

This becomes apparent when something breaks six months later. The original developer might be gone, or might not remember the details (because they never learned them in the first place). The code works, but no one fully understands why, or what assumptions it makes, or what edge cases it handles.

As one developer noted: “If you have to fix AI-generated code, this is a shitty job because the ‘creative’ part was done by AI, while the tedious part is on you. It’s the exact opposite of what we were promised.”

Why This Matters for Decision Makers

If you’re a CTO, technical lead, or engineering manager, you might be thinking: “So what? If the code works and we’re delivering faster, isn’t that a win?”

Here’s why it’s not that simple:

Technical debt compounds: Code that “just works” but lacks clear structure, proper documentation, and human understanding becomes technical debt. That debt accumulates interest in the form of slower future changes, more bugs, and higher maintenance costs.

Team capability doesn’t grow: When engineers rely on AI to generate solutions they don’t understand, they’re not developing the skills that make them valuable long-term contributors. You’re trading short-term velocity for long-term capability.

Review burden increases: Every AI-generated contribution requires more careful review because you cannot assume the submitter understands what they’ve created. This shifts burden from the contributor to the reviewers.

Maintenance becomes a crisis: When the only person who “knows” a system is an AI that won’t be available for support calls, you’ve created a sustainability problem.

The Path Forward

The goal isn’t to ban AI tools or to stigmatise their use. AI can be genuinely transformative when used appropriately. The goal is to ensure that AI amplifies understanding and capability, not just output.

In Part 2 of this series, we’ll explore practical approaches for CTOs, technical leads, and engineering teams to harness AI responsibly. We’ll look at how organisations like Fedora are creating policies around AI-assisted contributions, what “verification” should really mean in practice, and how to build engineering cultures where AI is a tool for learning rather than a crutch for avoiding it.

For now, I’ll leave you with this thought: Skelton was right that AI can amplify great engineers. Our challenge is ensuring it helps create great engineers in the first place, rather than enabling mediocre ones to produce more, faster.

This is Part 1 of a two-part series on AI amplification in software development. Part 2 will explore practical strategies for responsible AI use in engineering teams.